Engaged in the clothing industry for 20 years.

Rana Plaza – ten years later

How many times have we rolled our eyes when there was an emergency drill, maybe at school, work or college? Happening at the most inopportune times (just like a real emergency) – we may get up grudgingly, follow a dedicated co-worker or fellow student to an emergency meeting point and from there to the nearest exit. Grumbling about the interruption, we get back to where we left off because nothing happened.

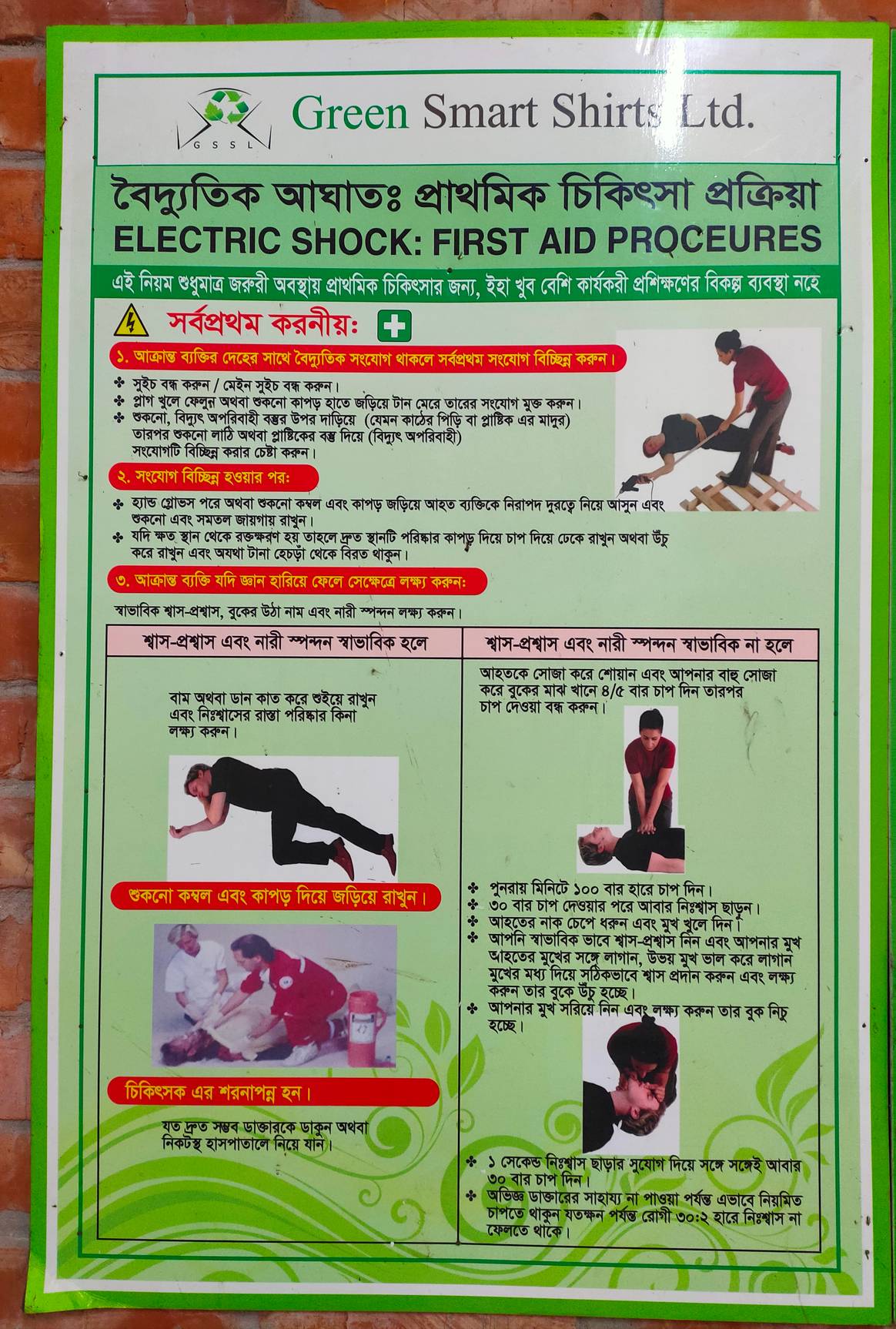

But still too often, something does happen and it is not a drill. In those cases, following a set protocol that has been revised and practiced regularly, can make the difference between life and death. This is the kind of training that would have spared the lives of more than 1,100 garment workers who died in the collapse of the Rana Plaza building on 24th April 2013, and saved more than 2,500 workers from debilitating injuries. It would have saved workers from harm when a fire at Tazreen Fashion broke out, and countless others in garment factories around the world that experienced fire hazards, explosions of gas cylinders, malfunctioning equipment and the like.

The tenth anniversary of the worst accident of not only Bangladesh’s garment industry but also the deadliest disaster in the history of manufacturing is a good time to look at the achievements over those ten years and what more needs to be done, not only in Bangladesh but in the industry worldwide.

The Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh

On 15th May 2013, not even a month after the Rana Plaza collapse, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh was signed: the first legally-binding agreement between global brands and retailers and IndustriALL Global Union, UNI Global Union and eight of their Bangladeshi affiliated unions. The aim was to work towards a safe and healthy garment and textile industry in Bangladesh and more than 220 companies signed it.

Established for five years initially, the Accord was extended by three years and then transitioned to the RMG Sustainability Council (RSC) in 2020. Since 2021, there is a new agreement, the International Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry, which brings the Accord to garment and textile producing countries worldwide.

With 220 companies signing the 2013 Accord, more than 2,000 factories were inspected, resulting in more than 40,000 initial and follow-up inspections. A staggering 150,000 safety hazards were found of which 93 percent have been remediated as of today. In fact, 400 factories have completed 100 percent of the necessary improvements. Overall, this work has impacted two million workers in these factories. “This has led to an industry-wide systemic change; Bangladesh is now one of the safest countries to source from in Asia,” said Joris Oldenziel, executive director of the International Accord Foundation, in a press conference organised by advocacy organisation Remake and the Clean Clothes Campaign in March.

The problems ten year ago

How could the situation deteriorate so much, why were the previous systems insufficient, which were basically the brands’ and retailers’ own codes of conducts? “The problems then [in 2013 and prior] were wide-spread, systemic. There were structural weaknesses, no fire extinguishers and more. Substantial expenses were involved to remedy the situation. Brands and retailers at that time were not ready to incur those financial costs and the related production slow-down,” explained Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium, at the press conference.

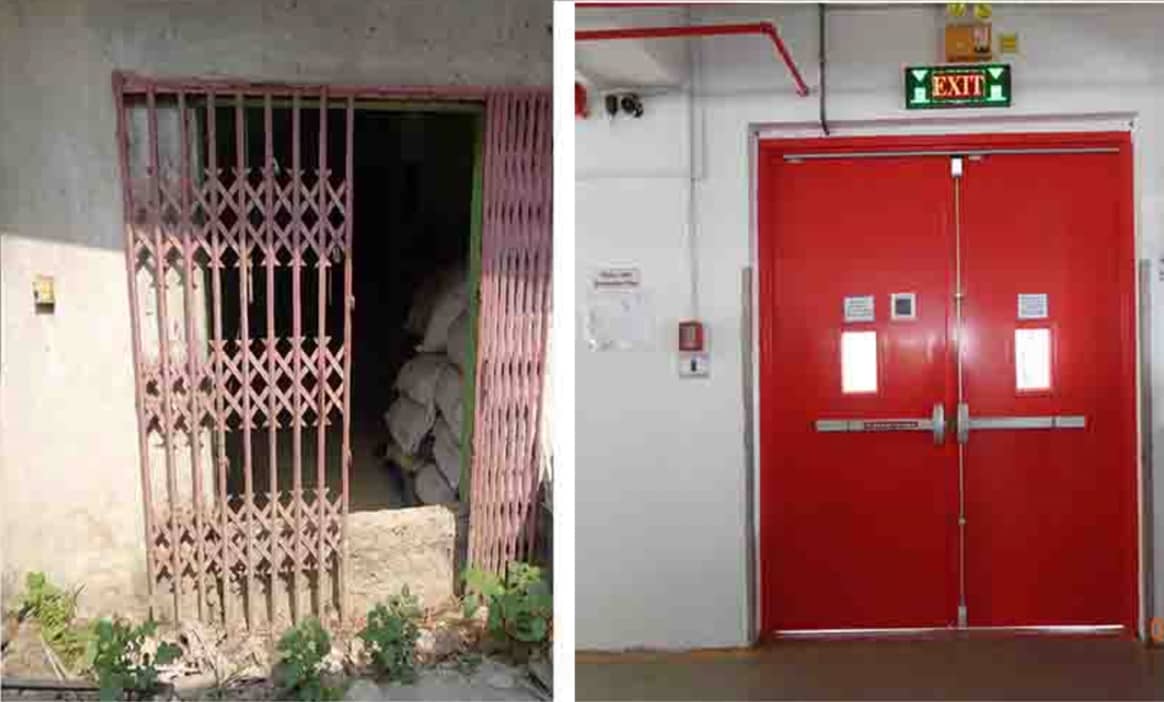

“Because they were not willing to fix the problem, they also had to downplay the problem,” added Nova. Two major safety hazards drove those mass fatalities: Structural columns not strong enough to hold up the weight of factory floors and a lack of adequate fire exit systems in multi-storey structures. That means, the real issues were not incorporated into the brands’ and retailers’ own safety protocols. “Because they were not looking for these issues, they did not find them and that is why, inspection after inspection got cleared without addressing the issues,” explained Nova. “That means, thousands of voluntary inspections were not even raising the essential questions. The Accord changed all of that”.

A game changer was the name itself – Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh – meaning that every time the Accord was mentioned formally, the key issues were spelled out. This binding agreement replaced the voluntary monitoring systems and opened factories up to competent inspections, with a first round happening in 2014: “This was the first time, that a trained, qualified safety engineer had ever sat foot into that factory,” emphasised Nova.

The Accord required factories to carry out whatever safety renovations had to be done and it obligated brands and retailers to ensure that the funds were there. In other words, “ the Accord delivered the components that were missing earlier,” said Nova. “Now, workers have achieved that they can say ‘no’ to unsafe work,” agreed worker rights activist Kalpona Akter who is also the president of the Bangladesh Garment & Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF). “Workers felt like they were just another part of the equipment, not human beings. Workers can now say freely how they feel about working in a factory. They can make use of the complaint mechanism without fear of losing their job.”

The International Accord

One of the signatories of the International Accord is US clothing company PVH Corp., which owns brands such as Tommy Hilfiger and Calvin Klein. PVH was also part of the steering committee of the Bangladesh Accord. “We have to see the International Accord as a model to expand to other countries, otherwise it will not mean a lot,” said Michael Bride, senior vice president of corporate responsibility and global affairs at PVH Corp, during the press conference.

It is an intricate interplay of inspections, worker involvement and joint governance with equal partners that leads to transparency. He explained how the complaint mechanism works from the brand’s side: “It is extremely useful and we take a complaint seriously and investigate,” which then leads to a discussion with the supplier. As that may sometimes not be very efficient, the Accord secretary can act as an intermediary and help the process along. The findings are then legally binding for brands and retailers. “Of 2,000 complaints, only one factory has been banned due to non-compliance,” reported Bride.

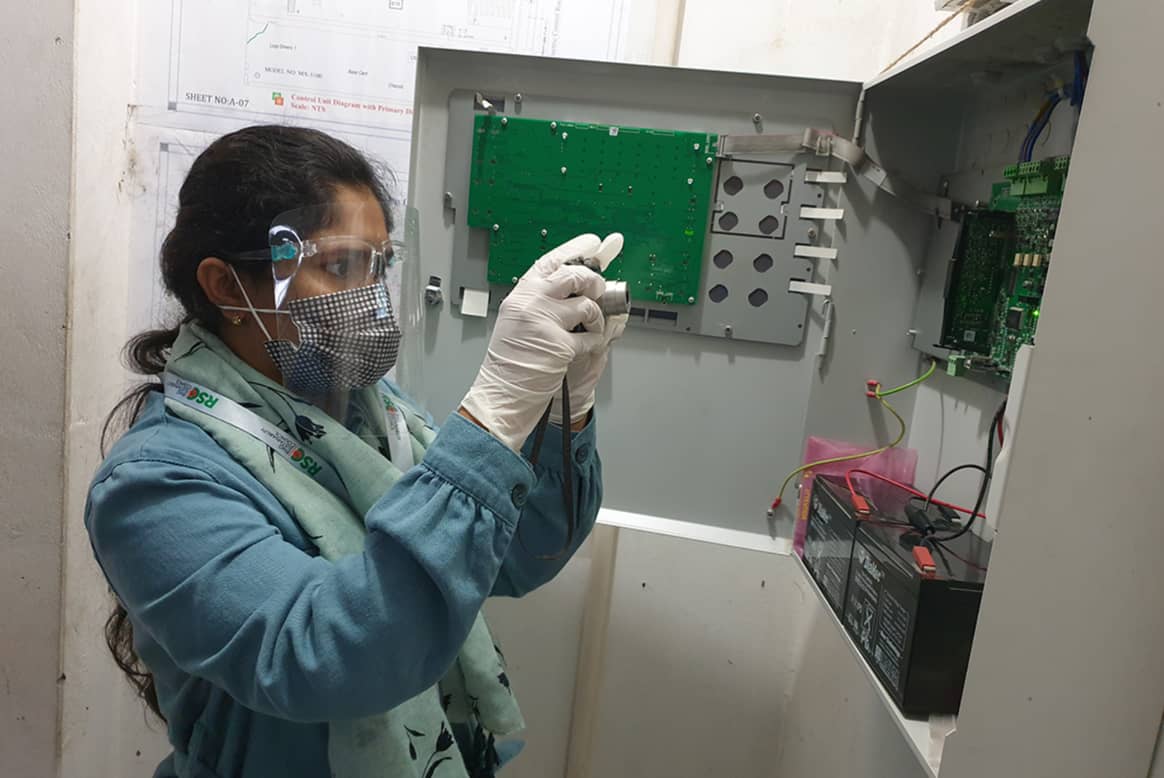

Asked about the nature of the complaints, Bride explained that there can be safety or non-safety complaints. The former relate to structural issues or occupational health including acts of violence. Bride recounted a case in which workers in one factory were complaining about electric shocks from sewing machines on the fourth floor. However, there was no fourth floor dedicated as a work space. Upon investigation, it turned out that the canteen on the fourth floor had been converted into a work area with sewing machines and the electricity supply had simply been extended from the second to the fourth floor, hence leading to the electric shocks.

The second type of complaints, non-safety ones, illustrate the need of workers to have an outlet for all kinds of grievances. The Accord does not have authority over those cases and passes them on to the brands and retailers directly. However, they are made public on the RSC website as part of an archive of complaints filed with and closed by the Accord and provide a current snapshot of issues at garment factories.

Going forward – what needs to be done

Though the achievements have been tremendous, there is much that still needs to be done, mainly in five areas: wages, gender-based violence, freedom of association and unionisation, environmental protection and compensation of workers affected by accidents. “While sweeping progress has been made in terms of building safety, there is very little progress in other areas of worker rights: wages are still dismally low, there are obstructions for workers to their legal rights to organise unions and abusive conditions in factories,” confirmed Nova. “Why so much progress in one area and so little in others? Because brands were willing to sign a binding agreement in one area but now we feel the effects of a lack of binding agreements in other areas.”

Survivors of the Rana Plaza collapse and other disasters like the fire at Tazreen Fashion are still finding it hard to sustain themselves and cope with the long-term effects of their injuries. Mahmudul Hasan Hridoy had only been working for two weeks at New Wave Style RMG factory on the eighth floor of the Rana Plaza building when the accident – which he calls “murder” – happend because the building was approved only for six floors, not ten. On the fateful day, he was stuck under the rubble with 17 other workers and is the only survivor. Apart from the mental trauma, there are physical long-term effects too that prevent him from working, making his family dependent on help from others. He demands that “brands should pay compensation, ensure rehabilitation and life-long medical treatment because we live an ‘inhuman life’.”

Nasima Akter had been working for Tazreen Fashion garment factory for four years when a fire broke out on 24th November 2012. She sustained severe injuries, including fractures on both hands, misplaced waist bones, a damaged neck bone, head injuries as well as impaired vision. Today, unable to work, she survives through the help of others, calling herself “a burden” and her life “inhuman”. She wants a dignified life and the life-time income and medical treatment that is legally owed to her.

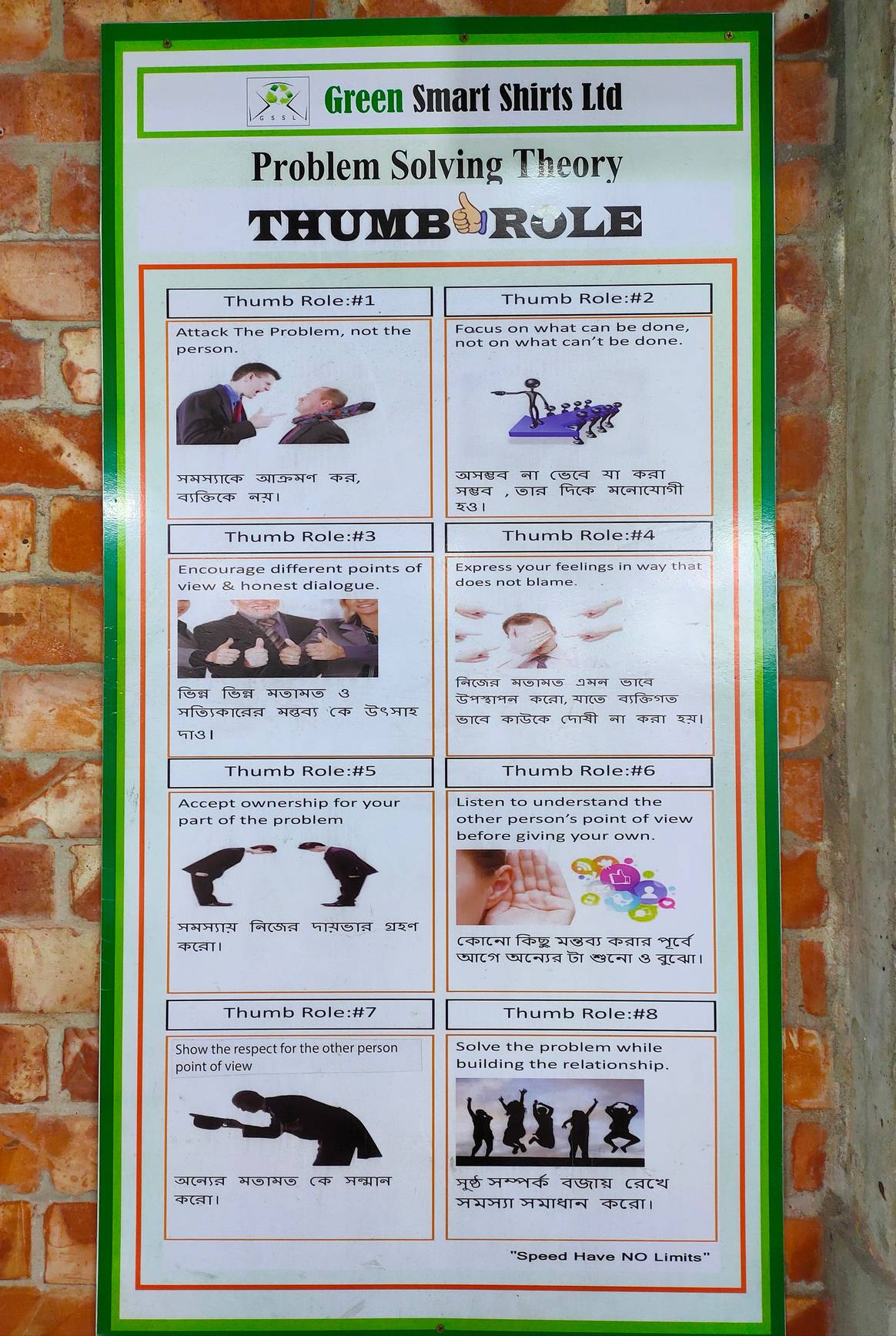

“My final request would be to buyers that when you give orders to a supplier, make sure that the factory has adequate fire safety measures including staircases, and make sure that the workers know how to handle an accident. Workers should also get practical training on evacuation, with fire drills at least twice a month so that in case of any accident, they can use their knowledge to come out safely,” pleads Akter in a video testimonial made available by Remake.

For those who have work, the situation may be only marginally better given that wages are still not living wages. “Wages remain far too low and are often not enough to live on. In Bangladesh, there has been no wage increase in the last five years. Amplified by high inflation, income in Bangladesh, as well as other countries in the global south, is not enough. Also, there is often no wage compensation when companies withdraw their orders, as was the case in the pandemic,” says NGO Femnet in an email.

The organisation that supports partner organisations in Bangladesh also calls gender-based violence in the workplace “a major problem”. “Workers must be better protected from this through reliable grievance mechanisms and legal counsel. The right to freedom of association and unionisation must be guaranteed by companies and factories,” it cautions. Another essential aspect is the environmental factor: “The global textile industry affects the climate and has a significant impact on the health of workers. Here, too, there must be binding rules to protect the environment and the climate through agreements and laws,” demands Femnet.

For Nova, the answer is clear: “If we want to see the kind of progress on wages, the right to organise and other issues, we need to apply that same model. We need binding and forceful agreements between brands and retailers and worker representatives to address labour rights issues across the board and not only in Bangladesh, but also in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the rest of South Asia and the rest of the world.”

The Pakistan Accord

Let’s look at how replicating the model is working out: The International Accord, along with its signatories and key stakeholders, has established a new country program in Pakistan in 2023, the Pakistan Accord. Till date, there are only 41 signatories, among them Aldi, C&A, H&M, Inditex, Kik, Marks & Spencer, Primark, PVH and Zalando. “We welcome the expansion of the International Accord into Pakistan to help promote decent and safe workplaces for workers. This move complements our own Structural Integrity Programme, which we have had in place in Pakistan since 2015, alongside our experienced team working on the ground who oversee the local implementation of our Ethical Trade and Environmental Sustainability programme,” commented Primark, one of the first signatories in February. The Irish discounter demonstrates how the new Accord can be integrated with internal programmes.

The point that the Pakistan Accord needs to garner more momentum was reinforced just ten days ago when a deadly fire at a factory in Karachi led to the four-storey building’s subsequent collapse, killing four firefighters and injuring 13 people. The fire at Usman & Sons Bedsheet Company in the New Karachi Industrial area was caused by a short circuit and rapidly spread and engulfed the stored clothes. As the factory was located in a highly congested area, firefighters faced difficulty reaching the factory with the appropriate equipment and putting out the fire.

Union leader Zehra Khan who joined the press conference from Karachi, drew a parallel from the deadly fire at Ali Enterprises on 11th September 2012 to the recent incident: “Accidents are still happening even though there is a health and safety council but it gets defied. Or decisions are made but no there is no follow-up.” She blames politics for this situation and stresses the importance of the Pakistan Accord.

“It will secure orders and will protect workers’ jobs. But we have to not only make it about building and fire safety, but also about occupational health and safety, gender violence and other current issues. We also need a strong monitoring system, complaint mechanism and remediation process. The Accord will bring transparency as brands and retailers have to share their suppliers,” added Khan, concluding that “the bottom of the supply chain should be included in our future and women workers should have the same rights.”

To push for the Pakistan Accord and to increase the number of signatories among brands and retailers, Remake and the Clean Clothes Campaign have since launched the #SignTheAccord campaign, demanding that twelve bands in particular that are central to its success in the country sign it. Those are Amazon, Asda, Columbia Sportswear, Decathlon, Ikea, JCPenney, Kontoor Brands, Levi’s, Target, Tom Tailor, Urbn and Walmart. While no brand can do it alone, the last ten years have shown how crucial their support is for sustainable, systemic change along all levels of the supply chain.