Engaged in the clothing industry for 20 years.

Why is it so hard to enforce a living wage?

In Germany, trade union Verdi is calling for a minimum wage of 13.50 euros (about 14.60 US dollars/11.50 British pounds) per hour in the retail sector – figures that garment workers in the Global South can only dream of. Why is it so difficult to introduce living wages in the textile industry and how could this be achieved?

Marian von Rappard owns textile factory Evolution in Vietnam, where he also produces clothes for his own jeans label Dawn Denim. There, he pays all his employees a living wage. Von Rappard is trying to promote long-term change in the fashion industry, most recently at the Fashion Changers Conference 2023.

Marian von Rappard started his career in the fashion world in 2009 when he set up his own business in Vietnam. His original idea of using a commercial agency to mediate between brands and factories quickly evolved into setting up a sample studio. There, he and his team designed collections with a small production volume and manufactured them themselves – his current factory grew out of this studio. In 2015, he then founded the sustainable jeans label Dawn Denim together with designer Ines Rust. All of the brand’s products are manufactured in the factory in Saigon.

“In our factory, we are establishing new standards for fairness and environmental awareness,” states Dawn Denim on its website. “We bear the responsibility for a fair and well-paid working environment. From the very beginning, we have decided to pay our team in Vietnam according to the Anker Living Wage method in order to secure livelihoods and enable dreams to be realised.” Via Tip Me customers can also send a tip to the workers in Vietnam.

To make the supply chain as transparent as possible, Dawn Denim shows the individual steps in the manufacturing process of the products on the product pages in its online shop. In collaboration with software company Retraced, customers can view the journey of a product from fabric processing to production.

The debate about pay equity in the textile industry has been omnipresent for years, but nothing really seems to be moving. The urgency for change was demonstrated by the devastating extent of wage protests in Bangladesh in October last year, when a textile worker was critically injured during a demonstration for higher wages and subsequently succumbed to her injuries. Fair wages – an issue that costs human lives and needs one thing above all for long-term improvements: More willingness to act from brands that produce in countries such as Bangladesh and Vietnam. There is still a lack of willingness to invest and take risks, as well as cooperation with like-minded people.

“To achieve living wages at the factory level, apparel brands and retailers must be willing to view their relationships with suppliers as a partnership,” comments the Global Living Wage Coalition in response to a question from FashionUnited. “Ultimately, they must be prepared to pay more for their products in order to achieve the common goal of fair pay for workers.”

As a statutory wage floor, the minimum wage sets the minimum that employers must pay their employees in order to fulfil their basic needs. “Ideally, the minimum wage should be the result of a tripartite discussion between representatives of the government, employers and employees,” says the Global Living Wage Coalition. However, it is often a government decision that is made without the involvement of workers.

According to the Partnership for Sustainable Textiles, this wage threshold is often not enough for a decent standard of living in the countries where the textile industry is based. This is precisely where the living wage comes in:

In comparison: Since January 2024, the minimum wage in Germany is 12.41 euros per hour (about 13.46 US dollars/10.57 British pounds). In Vietnam, the minimum wage ranges between 15,600 and 22,500 Vietnamese dong per hour depending on the region, which is the equivalent of 58 to 84 cents (about 0.63 to 0.91 US dollars/0.49 to 0.72 British pounds).

The International Labour Organization (ILO), based in Switzerland, estimates that 266 million workers worldwide are paid below the minimum wage, which corresponds to 15 percent of all employees. Minimum wages are also often not adjusted to changing economic circumstances such as inflation, which leads to wage losses.

Who defines a ‘decent life’?

The minimum subsistence level on which the living wage is based is very country-specific and can be calculated using various methods. Von Rappard uses the Anker method in his factory, which was developed by Americans Martha and Richard Anker.

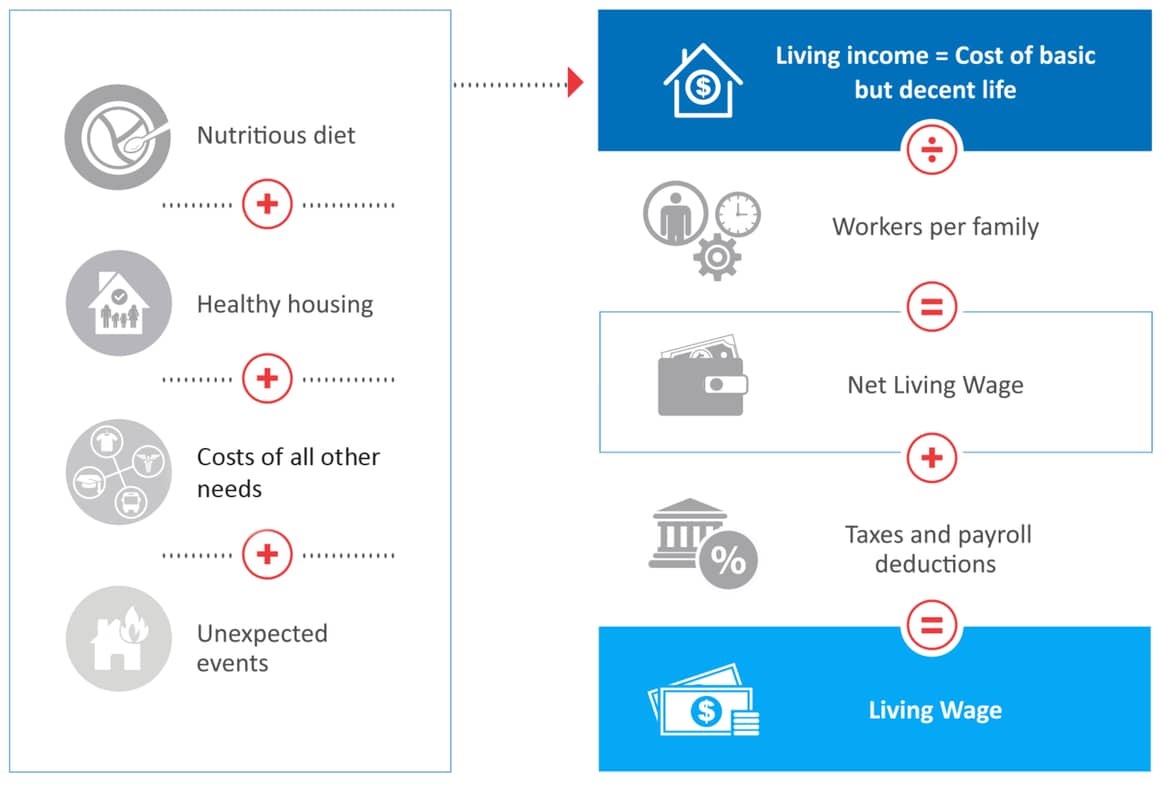

According to von Rappard, wages are calculated using this method in a “shopping basket system”. Costs for things like a ‘balanced diet’, ‘adequate housing’, ‘unforeseen events’ and ‘other needs’ such as clothing, education and healthcare are added to form the cost of living for a simple but adequate life.

There are special features that differentiate the living wage from the calculation of the minimum wage. For example, recommendations from the World Health Organisation (WHO) are used to determine food costs and combined with local data. To this end, country-specific food prices are regularly collected and analysed with the involvement of workers. Local data is also incorporated into housing costs, which are determined through flat viewings with employees.

According to the calculations using the Anker method, von Rappard would have to pay the employees in his factory a monthly wage of between 8.8 and 9.2 million Vietnamese dong (around 325.15 to 340.56 euros). The workers in his textile factory are paid an average wage of 8.5 to 11 million Vietnamese dong (around 314.39 to 406.85 euros), which is higher than the calculated amount. In addition, all employees receive private health insurance.

“Another key element is the availability of services and infrastructure that enable a decent standard of living,” says the Global Living Wage Coalition. According to a study by the Anker Research Institute, the living wage is lower if the costs of elements of a decent life, such as housing, transport, education and medical care, are also lower. In countries “where governments subsidise basic goods or provide high-quality public services, the living wage is lower and easier to achieve than in comparable areas that do not have the same level of government support.”

What is the problem

“Governments have a major role to play in ensuring that people can afford a decent quality of life,” explains the Global Living Wage Coalition. Their role is to provide for the needs of society. Furthermore, it is the responsibility of employers and buyers to respect the rights of workers – especially their right to fair pay.

Last year, around 600,000 garments were produced in his factory, von Rappard told FashionUnited. Only ten percent of these are for his own label, the remaining 90 percent are commissioned by other brands. “Dawn needs to grow so that our own production is more relevant in the factory and that we can then pay higher prices,” he states. In future, half of the production facility will be utilised for the manufacture of Dawn products. If the brand is more relevant, it will also be possible to renegotiate wages and prices.

According to von Rappard, a major problem stems from seasonal production, as so many factories are only utilised to a small percentage by many different brands, which means that the influence of the individual brands is lost. A brand would therefore have to take on a large production quota – or all labels that produce in the factory would have to be prepared to pay higher wages and therefore higher prices for their products.

Von Rappard wants his industry colleagues to work in partnership and be willing to pay more. If brands were to join forces to utilise 80 to 90 percent of production facilities, prices could be renegotiated. But this willingness to collaborate is exactly what the industry is lacking, says the factory owner. In addition, these projects are very risky from an economic perspective and therefore often unattractive for companies, which is often exacerbated by government regulations.

The future: Asian Floor Wage

The Asia Floor Wage Alliance is a labour and social alliance founded in 2017 that works to improve wages, combat gender discrimination and regulate supply chains in garment manufacturing countries.

The organisation also developed a method for calculating living wages for textile workers. It is based on three basic assumptions: Adult workers need 3,000 calories a day and must be able to feed themselves and two other so-called ‘consumption units’. In addition, the ratio of food costs to non-food costs is 45:55. The wage according to this method is earned for a maximum working week of 48 hours and is even higher than the wage according to the Anker method.

The payment of an Asian Floor Wage is also von Rappard’s long-term goal, but at the moment the founder is not yet able to afford these sums – this is exactly where his ‘call for calloboration’ from the Fashion Changers Conference comes in. In order to be able to pay its more than 300 employees in the Saigon factory a wage in line with the Asian Floor Wage, other brands must also be prepared to pay higher prices.

The Global Living Wage Coalition also emphasises the partnership-based cooperation between factory and buyers: “This is the only way to increase wages in a truly meaningful way”.

This article was originally published on http://FashionUnited.de . Edited and translated by Simone Preuss.